03 Nov Collection in action: Peugeot hillclimb special

South African car enthusiasts have been, are and surely will continue to be an amazing breed of people. FMM’s Peugeot hillclimb special has a classic example of South African ingenuity. Mike Monk takes to the hills…

Ever since the horseless carriage first rolled its wheels on our soil, locals have embraced the technology and despite being geographically a long way away from the birthplace of the motor car, have always shown an innovative streak. But perhaps it is only in today’s world that we can look back on some locally ‘built cars’ and appreciate what was then a case of a ‘boer maak ’n plan’ now stands as a proud example of engineering ingenuity. Take this Peugeot hillclimb special as a case in point…

It is based on the chassis of a late-’30s model 402, a remarkably swoopy and aerodynamic-looking vehicle available in a number of body styles, all with headlamps located behind a swept-back waterfall grille: certainly distinctive and quite a radical design for the time. However, this example did not survive too long because by the early 1950s it was languishing in a scrapyard from where it was rescued by Don Tout who, as we shall see, was a man on a mission and not short on ideas…

Don wanted a sports car but was not prepared to pay the asking price of ready-made examples so decided to build his own. According to historian Ken Maxwell who interviewed Don back in 1971, he was inspired by the pre-war 402 sports models that performed well in long-distance races and, more specifically, the two-seater special built by French Peugeot distributor Emile Darl’mat, which was, in fact, a coupé built on a 302 chassis but with a 402 engine.

Don removed the body, shortened the wheelbase and replaced the half-elliptic springs with quarter-elliptics. With 402 parts generally difficult to obtain, the chassis was fitted with brakes from a Dodge and a steering box from a Riley 9, the flat-spoke 402 wheels being retained. He then engaged a panel shop in Melville to make up a bespoke, all-aluminium two-seater body with a long, louvred bonnet, twin aero screens and rear fenders integral with the body. But far from being an uncoordinated ‘back yard bitsa’ build, Don applied sound engineering skills to his project, witness the neat engine-turned dashboard with all its gauges – oil pressure, boost pressure, oil temperature and water temperature.

The four-cylinder 2 142 cm3 44 kW poppet-valve engine (early 402s had a 1991 cm3) was reconditioned with pistons of a British make, possibly from a Triumph, the cam modified to drive a Lucas distributor and an oil pump, of undetermined origin but bearing a similarity to that of a Bedford. The overhead valve rockers and adjusters are British, Whitworth Fine threads and all, and there’s an Austin starter and a Jaguar radiator. But the most remarkable modification was the addition of a supercharger, but not your usual Roots-type blower, oh no…

Output enhancement was in the form of a 750 cm3 cabin blower taken from the Merlin 76 engine of a de Havilland Mosquito WWII combat plane, the blower adapted to act as a supercharger fitted with twin 1½-inch SU carburettors. Geared to run at two-and-a-half times engine input speed, it required an oil cooler to lower lubricant running temperature from 140 to around 85 degrees.

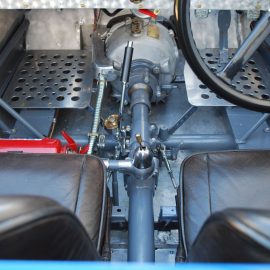

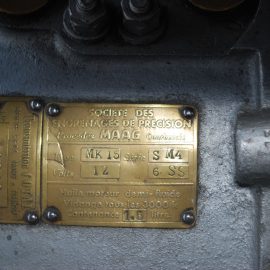

Yet another remarkable part of the car’s make-up is the transmission, a Cotal four-speed automatic, which was only an option on the 402 and a not very popular one at that, so making this quite an unusual application. The Cotal’s electric gear change was moved from the steering column to between the seats, which came from an Austin 7. The diff was not standard 402 but described by Don as being from a “sports Peugeot” when interviewed about the car by Maxwell. Despite the diff’s higher-than-standard ratio – 37 km/h per 1 000 r/min in top gear – acceleration in the gears was “very good” according to Don. It was a relaxed cruiser that could rev to 4 000 in top on the flat but spin beyond that on the downhills. Don did not compete in circuit racing but took part in a number of hillclimbs before, surprisingly, selling the car soon afterwards.

The history of the ‘bitsa’ Peugeot from then is not known until the Heidelberg Museum obtained the car in 1979. When Heidelberg was closed, the collection was incorporated into and transferred to the Franschhoek Motor Museum and the car made a number of select appearances before 2009 when it performed demonstration runs at the inaugural Knysna Hillclimb, driven by FMM curator Wayne Harley.

Afterwards, it underwent a ground-up restoration. Restorers Steven and Graham Mesecke were instrumental in uncovering some more interesting facts about the car. For starters, the chassis has been three different colours in its lifetime, starting out as grey then yellow and finally black. It was also determined that the car originally had a red body and only later did it become the French racing blue it is today. And at some point the rear fenders were replaced with the cycle-type mudguards that are now on the car.

Resplendent in its striking blue paintwork and with more louvres than your local DIY store, the Peugeot has real presence. The racing roundels carrying number 39 are in recognition of the year the original chassis was built. Aero screens offer token wind protection and running along the driver’s side bodywork – just below elbow level – the chromed, unsilenced exhaust is as ‘straight through’ as you can get. Inside the cockpit everything mechanical is exposed: there are certainly no sops to luxury save leather upholstery for the pair of tiny bucket seats. The engine-turned instrument panel contains a surprising number of gauges, including oil pressure and temperature.

Climbing in is aided by a removable steering wheel held onto the keyed column by a spacer and a giant wing nut – placing the spacer either behind or in front of the boss constitutes adjustable steering. The steering is very heavy and direct, compensated to a degree by the amount of leverage afforded by the classic upright, close-to-the-chest wheel position (not to mention the proximity of that wing nut…). Firing up, the motor bursts into a raucous crackle, spitting and barking with considerable menace. A push/pull knob – in for forward, out for reverse – selects the desired direction of travel (all the gears work in both directions). A conventional handbrake stands alongside the Cotal’s tiny selector switch and with first gear pre-selected, I cautiously depress the central accelerator pedal and I am away, quickly off the mark thanks to the low gearing.

Flick, flick and into the higher gears with modern autobox alacrity and the Peugeot gets quicker, louder, hotter and slightly easier to steer. Being aware of the front wheels jiggling over the bricked roadway highlights the stiff suspension set-up and the whole driving experience is very involving. A rudimentary bonnet scoop directs air onto the driver’s feet but on this mid-30s summer’s day drive has little cooling effect. With a still-tight motor and no rev counter, I was not prepared to push the car too hard. Easy through the bends, too, as this was one of the rebuilt car’s early outings but especially through the right-handers, elbow out (mind the exhaust!), did evoke plenty of images of war-time racing heroes man-handling their machines with spirit – and not a little skill. To a mere mortal today, their exploits simply beggar belief.

At the end of the day, switching off and listening to the hot metal tick-ticking in a kind of mechanical perspiration, I was left awestruck by what Don Tout not only produced but drove to the limit on some of SA’s demanding and infamous hillclimb venues. This Peugeot is certainly not for the faint-hearted but the sheer thrill of heading to the hills in such a one-off special is ‘Boys Own’ material.

Visitor note: The Peugeot Hillclimb special is currently on display in Hall D.