29 Apr Collection in action: DKW Cabrio

Mike Monk goes ‘two-stroking in ‘a little Horch’…

Wherever a DKW appears it naturally draws smiley attention. Start the engine, and with the requisite fanfare of an oily two-stroke puff of smoke, the two-cylinder engine pings into life and immediately settles into a distinctive and melodious ‘rat-a-tat-a-tatter’ idle that sets it apart from all other internal combustion machinery. The effect can perhaps be best summed up as character, which even in its day was something to be admired – and certainly enjoyed.

The letters DKW stand for a number of things. In 1916, Danish engineer Jørgen Skafte Rasmussen founded a factory in Zschopau, Saxony, Germany, to produce steam fittings as well as a light steam-driven car, called the DKW – Dampf-Kraft-Wagen (steam-powered-vehicle), which, however, was not a success. Then in 1919 he made a two-stroke ‘toy’ engine called Des Knaben Wunsch (‘the boy’s wish’), a modified version of which was fitted to a motorcycle that was dubbed Das Kleine Wunder (‘the little wonder’), which finally established the initials DKW as the brand name. This was a very important development because by the early-1930s DKW was the world’s largest motorcycle manufacturer…

In September 1924, DKW bought the electric car manufacturer SB Automobilgesellschaft mbH, following which Rudolf Slaby became DKW’s chief engineer. In 1923, the SB was also offered with the DKW engine but neither car was a success and the company folded in 1924. In May 1928, the first DKW car, the rudimentary Typ P, emerged from the Spandau, Berlin plant followed by the Typ 4=8 but, more significantly, Rasmussen became the majority shareholder in Audi Werke AG in Zwickau. It was here that DKW’s F series of ‘people’s cars’ began to emerge in 1931, but the following year the company merged with Audi, Horch and Wanderer to form Auto Union, the forerunner of today’s Audi AG, which has to this day the four-ring Auto Union badge as its own emblem.

Beginning with the F1 in 1931, the F – for Front – series were the first volume production European cars to feature front-wheel drive and created a pre-war boom in popularity for the marque. The F5 series appeared in 1935 and along with two saloon models, the range comprised a Reichsklasse, a 35-mm longer Meisterklasse, a two-seater cabriolet and the lighter-bodied Front Lexus Cabriolet and Sport, which boasted steel-clad bodywork rather than fabric.

The body plate under the centrally-hinged bonnet reveals that FMM’s car is an F5-700 (number 5017189) and it is registered as a 1938 model. Another body plate states that the body was manufactured by Horch (number 1874), and as a result these Front Lexus Cabriolets were known as the ‘little Horch’.

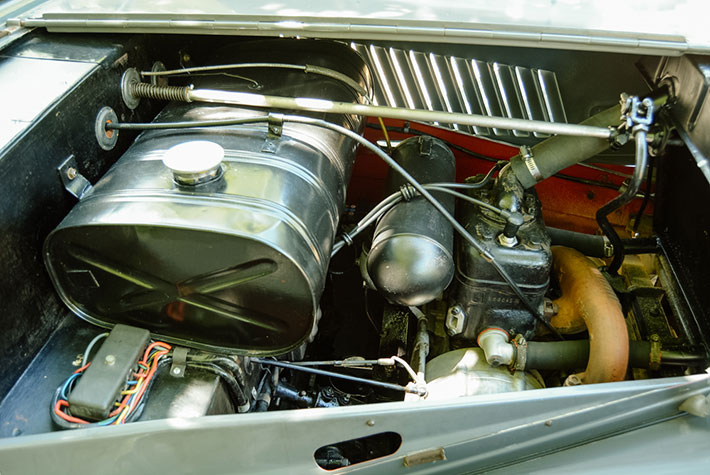

The Reichsklasse was powered by a 584 cm3 version of the transversely-mounted two-stroke twin-pot that produced 13 kW while the rest of the range boasted a 692 cm3 engine delivering 15 kW at 3 500 r/min. Strangely though, the body plate shows an engine capacity of 684 cm3… Respective top speeds were 80 km/h and 85 km/h, although 95 km/h was claimed for the Front Lexus models. A three-speed manual gearbox was standard on all models, the L-shaped gear lever sprouting horizontally from the dashboard. Incidentally, in 1947 the engine design was adopted by Saab in Sweden for its Saab 92 and also formed the basis for engines used by East German manufacturers Trabant and Wartburg.

Rear-hinged ‘suicide doors’ open to allow easy access to the leather bucket seats, which offer plenty of fore-aft adjustment. The passenger seat even has backrest angle adjustment, courtesy of adjustable leather straps attached to either side of the cushion. There is no rear seat but carpeted storage space instead; the back of the passenger seat tips forward to help load bulkier items. There is a small boot that increases luggage capacity, while the spare wheel is attached to the rear of the body lid under a cover, ‘continental’ style.

With the hood erect, which is secured by two clips on the windscreen header rail, the screen itself can be opened from the bottom to create some through-flow ventilation. The motor driving the windscreen wipers is mounted on top of the dashboard and when the screen is closed, its drive shaft clips into the left-hand wiper spindle that is externally linked to the right-hand blade. All very simple and basic.

There is no B-pillar, and side windows wind down completely into the doors. On a clear Cape summer day, the DKW’s fabric top was folded back in order to savour the midday sun with some al fresco motoring. However, ‘folded back’ is a bit of a misnomer as there is no inner-body storage for the top, which is flanked by ornate perambulator-like hinges. The top then serves as a kind of spoiler that doubtless creates considerable aerodynamic drag – or should that be downforce? Either way, it must reduce top speed but in reality this is hardly significant. Oh, and rear view vision is non-existent, not that it is much better with the top erect as the window is short and narrow.

Turn the key (electrics are 6-volt) and depress the floor-mounted starter button – easily confused with the headlamp dip switch on first acquaintance – and that oh-so-charismatic motor comes alive. Unlike Citroën’s similar pull-push gear shift as used in the 2CV, the DKW’s control is easier to operate from the get-go, a short reach from the rim of the three-spoke steering wheel. The car pulls away with ease and the engine note fizzes and pops as revs rise en route to top gear being selected, at which point the mechanical noise becomes subdued and the car becomes an autobahn cruiser. Semaphore indicators announce an intention to turn. Riding on 17-inch wire-spoke wheels, the leaf-spring suspension provides a remarkable supple ride with relatively little roll.

Published figures suggest that around 218 000 DKWs, of which 85% were the F series cars, were produced in Zwickau between 1931 and 1942. By 1934, DKW sales placed the company as Germany’s second biggest motor manufacturer, and by 1938 accounted for more than 16% of the market. It is not difficult to understand why. The F series DKWs offered a simple and affordable mode of transport for the masses that also managed to be a pleasure to drive. ‘Rat-a-tat-a-tat…’