03 Aug Collection in action: BMW

Far more than a flight of fancy, in the early post-war years and with the help of Frazer Nash, the Bristol Aircraft Company started to build some individualistic Grand Touring cars powered by BMW.

In the aftermath of World War Two, The Bristol Aeroplane Company decided to diversify into automobile manufacture and towards the end of 1946 announced its first car, the 400, with production slated for the following year. It was one of Britain’s very first post-war new cars, and its short gestation period was down to the fact that the company obtained a licence from Frazer Nash to build BMW-based cars, which, in turn, had acquired the right as part of war reparation from Germany. So, rather than having to start with a ground-up design, Bristol was able to draw on the BMW 326 (chassis), 327 (body) and 328 (engine) models to create the 400.

In 1947 BMW’s talented engineer Fritz Friedler – the man behind the six-cylinder 326/327/328 cars that paved the road to success for BMW – left his senior post at the company to join H J Aldington’s AFN (Frazer Nash) Ltd but was almost immediately loaned to Bristol as a consultant for the 400’s development. After three years with AFN, he returned to BMW where he became chairman of the company from 1955 to 1956 before retiring in 1966. Little wonder then that the Bristol was a success from the outset.

The 400’s styling differed only slightly from that of its Bavarian-built donor designs, the kidney grille and close-set headlamps doing little to disguise the fact. Either way, they are all handsome designs that have stood the test of time and today are all considered classics. The car was immediately recognisable as a grand tourer, its long 114-inch (2 896 mm) wheelbase, centralised chassis lubrication, transverse independent front suspension and precise rack-and-pinion steering endowing it with excellent road manners for its time. Brakes were well up to their task, too. It is perhaps a testament to both company’s aircraft industry roots that aerodynamics figure in each model’s flowing, low-drag design and quality build standards are evident throughout.

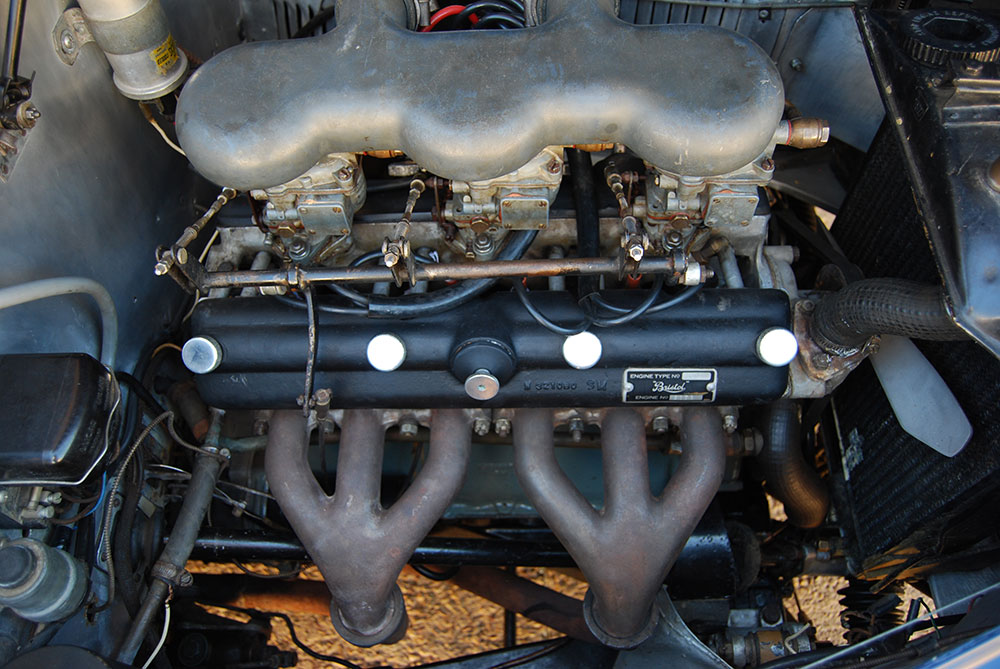

Part of the licencing deal included use of BMW’s superb 1 971 cm3 straight-six overhead-valve engine that with a single carburettor delivered 80 bhp (59,6 kW). Acceleration to 60 mph (96 km/h) took a leisurely 19,1 seconds, which belies its sporty nature, and top speed was 90 mph (144,8 km/h), a gait that the 400 could maintain all day long, suggesting overall gearing was chosen for cruising rather than sprinting.

The 400 was joined in 1949 by the 401 that featured an even more aerodynamic (no door handles, for instance) full-width body, still with headlamps flanking the now shortened kidney grille. The Aerodyne design, with its teardrop tail, was constructed using Carrozzeria Touring of Milan’s Superleggera principle of lightweight aluminium panels attached to a steel tubular space-frame. This allowed for a convertible to be made – the 402 – but only 23 were ever built and were bought mainly by the rich and famous, including actress Jean Simmons. Twin-carbs pushed power up to 85 bhp (63,4 kW) that helped reduce the 0-60 mph time to 15,1 seconds and raise top speed to 98 mph (157,7 km/h). Respected English motoring weekly The Motor said the 401 was “a car in a class of its own”.

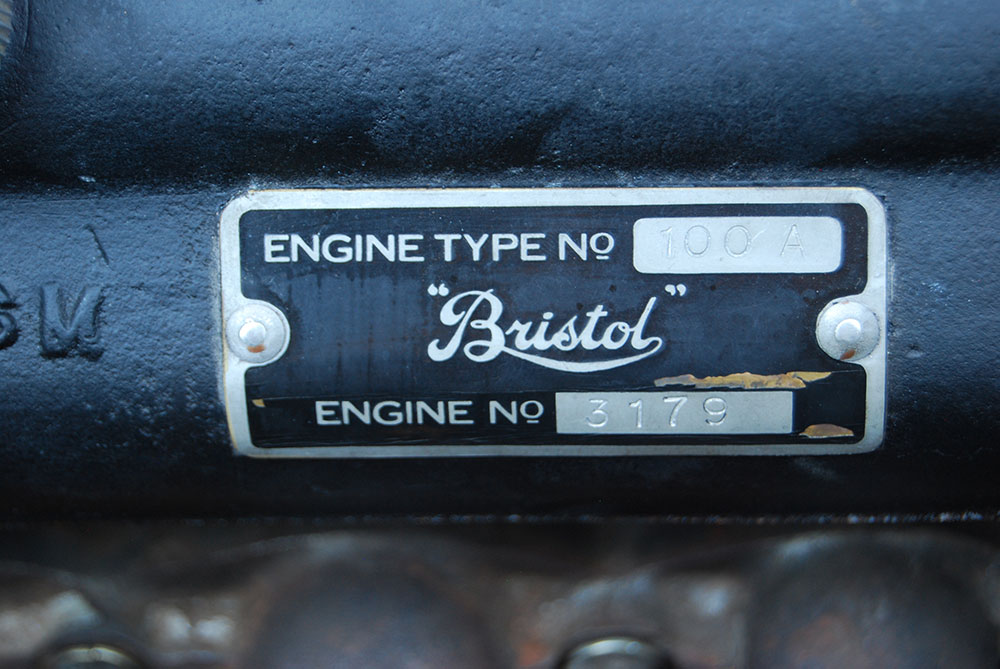

Building on such accolades, the 403 was introduced in May 1953, being effectively a tweaked version of the 401, identifiable by four headlamps, a silver grille and 403 badging on the sides of the sideways-hinged bonnet. The engine received bigger valves, larger main bearings and triple carburettors that contributed towards a power increase to 100 bhp (74,6 kW), which dropped the 0-60 mph time to 13,4 seconds and lifted top speed to 104 mph (167,4 km/h) – making it a genuine ‘ton up’ GT although no road tests appeared to substantiate this claim. Alfin (aluminium finned) drum brakes were used all round and a front anti-roll bar was fitted. Incidentally, 20 years after the 403 appeared it was reported that only four cars of the day had a better aerodynamic drag figure than its 0,4 Cd, which accounted for the model’s characteristic low wind noise.

The 403 is a striking car, the deep blue paintwork of the FMM’s example emphasising the flowing lines, the two-door body disguising the fact that it is a practical four seater – five at a pinch. It is a big car – 4 864 mm long, 1 702 mm wide and 1 524 mm high – but the proportions are so good that it does not appear cumbersome, the sloping rear and large side-glass area helping to balance the long bonnet.

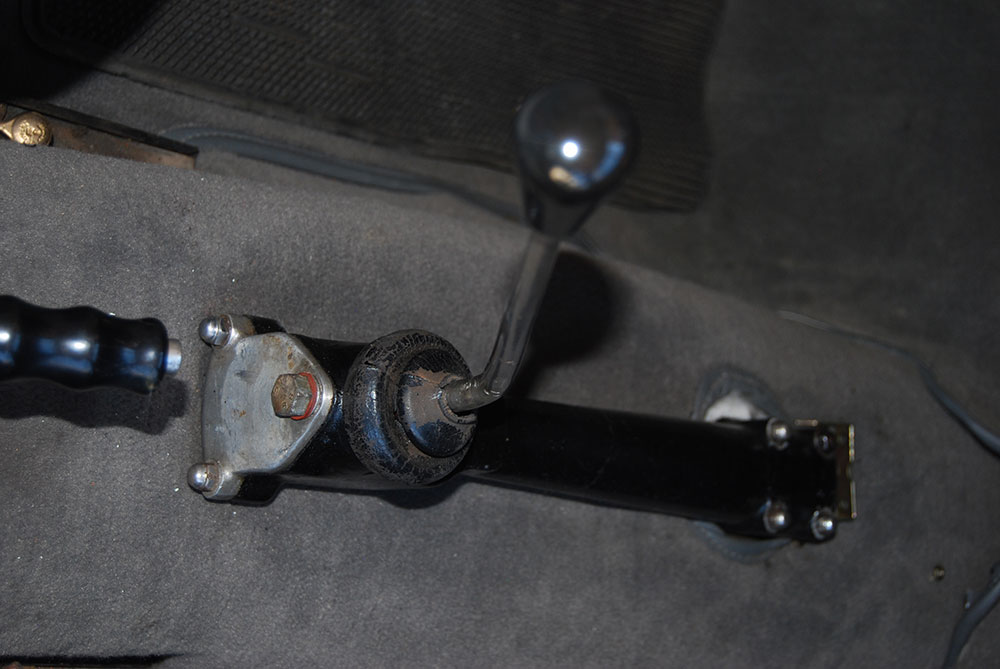

Step inside – the 403 retains a slightly vintage ‘sit on’ rather than ‘sit down’ seat height – on the generous leather-upholstered chairs and take in the full-width wood dashboard that carries a full range of instruments. The square-ish rev counter is positioned in front of the driver and the matching speedo facing the passenger, the needles of both rotating counter-clockwise. The steering wheel’s two spokes droop like a moustache but overall it is a welcoming and comfortable cabin. A synchromesh gearbox with a long lever was carried over from the 401, but during the 403’s life a remote shift with a shorter, more precise lever was employed, as fitted to this car.

Twist the key, press the starter and that classic straight-six crackles into life and somehow immediately awakens the senses. Engage first, pull away and the sensation heightens. None of the controls are heavy to operate, and looking at the road ahead through the fairly shallow split windscreen and down that distinctive bonnet heightens expectations. I can imagine owners blasting through the twisting English countryside to an early-morning cross-channel ferry and emerging in Europe for a flat-out inter-continental run along unrestricted motorways to a luxury leisure destination, arriving relaxed and unruffled, the car taking it all in its stride.

Today, the 403 is still a rewarding car to drive. Accept that it will be out-performed – but not out-run – by even modest family transport, the Bristol has an undiminished elegance about it both inside and out that makes any journey a pleasurable task. Sure, the steering is a little heavy and the turning circle of just over 11,4 metres makes for arm-rippling manoeuvring, but on the open road its stability, engine pulling power and well-tuned suspension, allied with excellent brakes, make for highly composed progress. The 403 defines Grand Touring and represented a bespoke alternative to rivals such as the Aston Martin DB2/4.

The 403 was only in production for two years and was the last Bristol to carry the kidney grille. The subsequent 404 boasted a new body style but the earlier cars’ attributes and accolades continued. The 400 to 403s were built at a rate of between 100-150 units per year – no more than 300 403s were made – and were expensive but soon established a loyal following that continues amongst active enthusiast clubs.

(While certain lockdown restrictions still apply on movement and accessibility, this story is based on my article that first appeared in the Apr/May 2013 issue of Classic & Performance Car Africa magazine – MM.)