30 Mar Collection in action: Austin-Healey 100M

Mike Monk gives the background to a big-hearted four with a link with the Circuit de la Sarthe…

When it comes to defining the quintessential post-war British sports car, the Austin-Healey will figure high in most people’s minds. The long bonnet, short tail, lusty engine, basic and robust drivetrain is typical of the Bulldog breed, the whole culminating in a grin-inducing, bugs-in-the-teeth, seat-of-the-pants driving experience made all the more pleasurable when wearing a cloth cap and string-back driving gloves. That the car went on to achieve success in such romantic and iconic events as the Monte Carlo Rally and Le Mans merely added glitz and glamour to the car’s persona – not to mention pride of ownership.

The Big Healey was the brainchild of Donald Healey who set up his own motor company at the Cape Works in Warwick, England at the cessation of WW2 in 1945. Five years later, engineer and stylist Gerry Coker joined Healey and they began work on a car aimed at fitting in-between the dated but cheap MG TD and the fast but (relatively) expensive Jaguar XK120. Donald’s son Geoffrey designed a box-section chassis and the Austin A90 powertrain was adopted, the 2,66-litre in-line four-cylinder engine left standard but the four-speed gearbox was modified by blanking-off first and fitting overdrive on the top two ratios.

At the 1952 Earls Court Motor Show the Healey Hundred – so-called for its ability to reach 100 mph – was unveiled and immediately pounced upon by none other than Leonard Lord, the head of the Austin Motor Company and who was in need of a sports car to supplement his company’s model range. A deal was struck immediately and the car – designated BN1 – was renamed overnight as the Austin-Healey 100 with full production slated for starting in 1953 at Austin’s plant in Longbridge, Birmingham – the first 19 cars (all left-hand drive) were made in Warwick with bodies built by Jensen.

Versions of the car soon began establishing speed records. To herald its US launch (exports were vital to Britain’s economy at the time), a modified version went to the famous Bonneville Salt Flats and averaged 122,91 mph (198 km/h) for 12 hours, 104 mph (167 km/h) for 24 hours and covered the flying mile at 142,64 mph (229,5 km/h). In 1954 the 24-hour average was raised to 132,29 mph (213 km/h) and a supercharged 100 covered the flying kilometre at Bonneville at 192,74 mph (310 km/h).

From such exploits the 100S (for Sebring) was developed featuring Weslake-designed cylinder heads that helped raise peak power from 67 to 98,5 kW, a four-speed gearbox without overdrive and a light-alloy body shell. Five cars were hand built specifically for development and racing by the Donald Healey Motor Company back at Warwick. Stirling Moss raced one in the Sebring 1954 12-hour race where he placed third, and the car finished 6th in ’55 and 11th in ’56. Other cars were entered in the Mille Miglia and at Le Mans. A production version was introduced in 1955 and was the first production car to be fitted with disc brakes front and rear. Only 50 were made with most exported to the USA.

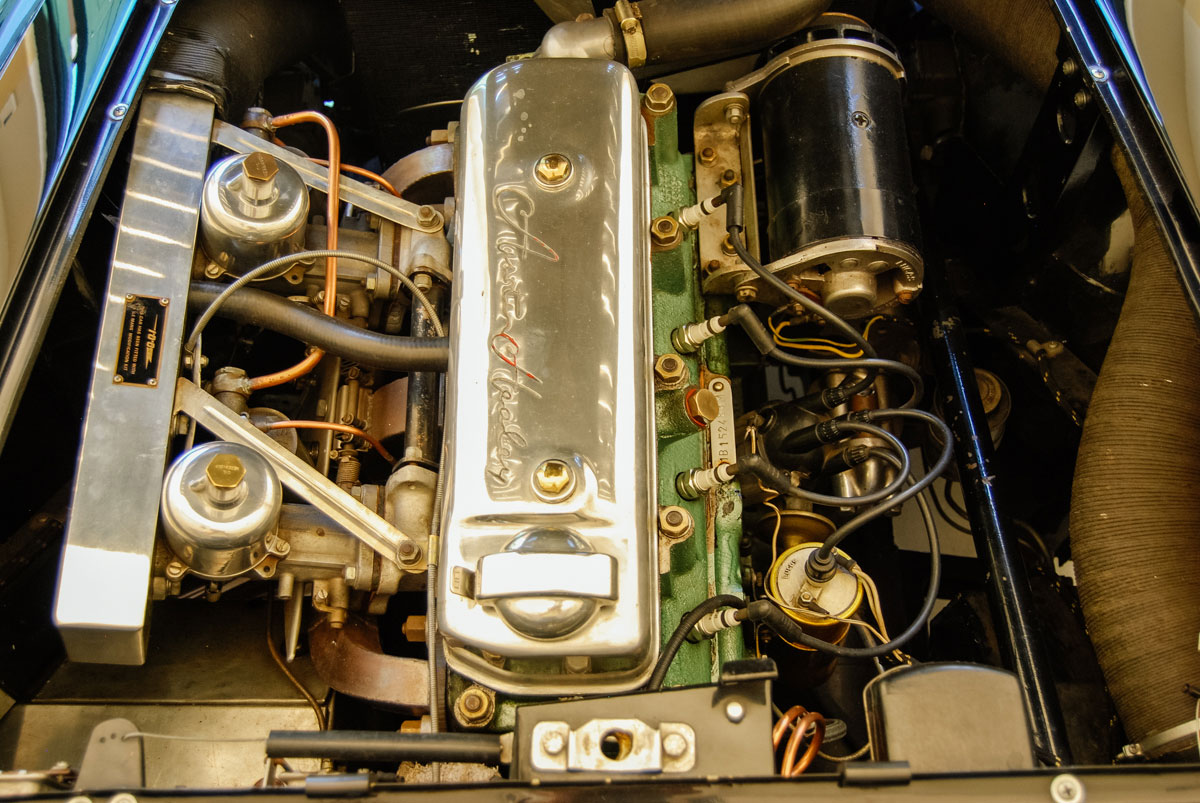

In turn, the 100S led to the 100M, a term denoting a performance upgrade that could be fitted ex-factory or by the dealer. The Le Mans Engine Modification Kit (to give it its full title) included twin SU H6 carburettors linked to a cold air-box to increase air flow, a high-lift camshaft with stiffened valve springs, a modified distributor and different pistons that raised the compression ratio to 8,1:1. The motor produced 110 bhp (82 kW) at 4 500 r/min and 217 N.m of torque at 2 500. A stiffer anti-roll bar was applied to the front suspension and the bonnet gained louvres along with a Le Mans-compulsory leather strap. The 100M could reach a top speed of 176 km/h.

The 100M’s running gear consisted of a simple ladder-frame chassis with a suspension set-up comprising of wishbones and coils springs up front and a rigid axle affixed to semi-elliptic leaf springs at the rear, with drum brakes all round. Wire-spoke wheels with spinners were de rigueur sports car fare of the time.

Later in 1955 – a busy year in the big Healey’s history – the BN2 version was introduced with a proper four-speed ’box with overdrive, a different back axle, bigger brakes and the option of two-tone paintwork. The front wheelarches were slightly larger, too.

It is one of the few late-BN1 100M cars (one of only 1 159 built) that is part of the Franschhoek Motor Museum’s collection. Adorned in black paintwork, it certainly looks the part – low, wide and handsome. The doors have no handles – to enter, reach over and pull on the leather pull cord and step down into the cockpit. Down is the operative word here, and I recall the first time I ever sat in one. I was a nipper and managed to get into one at a motor show stand and was totally amazed at the legs-out-straight seating position, which was a far cry from that of my Dad’s Hillman… This time it was not so unnerving and actually put me right in the mood, the upright, large wood-rimmed wheel positioned period-typical close to my chest, all the better for heave-ho-ing the cam-and-lever steering. Pedals are slightly offset to the right but not awkwardly so.

The view over the long, louvred bonnet with its leather strap coupled with my imagination and sense of the occasion turned every straight piece of road into the Mulsanne and any switchback corners became Maison Blanche (White House). Firing up the throaty engine sends tingles through the body – both the car’s and the occupants’. Being so low slung, the exhaust system passes just below the seat pans so its rorty sound effects are felt almost as much as they are heard – both being sensory delights.

Being able to look through, rather than over, the windscreen made for comfortable top-down progress but eventually I could not resist the temptation to use the rather clever folding mechanism to lay the glass down horizontally, which simply meant the air flowed straight into my face… But the car looked far more sporty and the revised aerodynamics actually contributed to a higher top speed (by around 10 km/h it is claimed).

The undersquare (bore 87,4 mm x stroke 111,2 mm) ‘big four’ engine may have commercial origins but perhaps partly explains its tractability – it pulls without fuss from any speed in any gear. Adapted from a column shift, the gear lever sprouts from the passenger side of the transmission tunnel with a gate that is back to front: remembering the proper first is blanked-off, ‘new’ first is dog-leg right and back below the easily-engaged reverse, with second and third to the left and overdrive for these activated by a toggle switch on the dashboard. Engagement is easy, not that there is much need once up and running.

Put your foot down and the 100M feels really quick – 0-100 km/h in less than 10 seconds – despite it having no energy once the three-bearing crank was rotating past the 4 500 peak power r/min. Being so low-slung, the ride is hard (the grab handle for the passenger is not there for show) but there is little obvious body flex or scuttle shake and barely any roll either. Rolling on fairly skinny 15-inch tyres, steering is quite direct and effort lightens up with speed. There is a kind of post-vintage feel to the driving experience, the tail ready to step-out with boyish enthusiasm with little provocation. Brakes need a firm shove but are effective enough.

In 1956 the four-cylinder Healeys gave way to the 100-6, which had a lengthened wheelbase, altered bodywork, a fixed windscreen, +2 seating and BMC’s C-series six-cylinder engine with a four-speed ’box with overdrive. Later versions went on to become rallying legends in the hands of Don Morley, Pat Moss, Rauno Aaltonen and Timo Mäkinen. The sixes were a step up from the fours but there is a rawness and sense of purpose about the earlier cars that is hard to ignore. With wind buffeting your face, the 100M has that priceless smile-on-your-face quality – it just feels so right, not so much in what it does but rather the way it does it. A truly classic British sports car.

(This article originally appeared in the February/March 2013 issue of Classic Car Africa magazine – www.classiccarafrica.com)