25 Jul Collection in action – S

An alphabetical series of short driving impressions of some of the museum’s car collection. This month we symbolize S with a model that was a part of an ongoing life-line for one of America’s independent automakers.

Studebaker is one those American car companies that tried hard to stay independent but, through circumstances often beyond their control, fell by the wayside in an attempt to stay with the Big Three – Chrysler, Ford and General Motors. Yet Studebaker, whose origins date back to 1852, had a proud history and was not short on innovation but simply could not sustain itself despite an early reputation for quality and reliability.

For the most part, however, the company operated under financial difficulties and weak sales in 1938 looked ominous. To turn matters around, the following year the first-generation Champion was launched and hopes rested on its success. A ‘clean sheet’ design, the Champion was conceived partly with the aid of market research and its most notable feature was weight – it was one of the lightest cars of its era. The Champion was a success thanks to its low price (US$660 for the base model two-door business coupé), robust engine and good looks, the latter the work of renowned French-born industrial designer Raymond Loewy. Powered by a compact side-valve, four-bearing 2 692 cm3 straight-six engine that was to last another 25 years, the Champion also proved to be economical, winning the Mobilgas Economy Run. During the war years when petrol was rationed, the car’s fuel economy, which was around 8,6 litres/100km, was a major plus-point. It was the company’s best-selling pre-war model.

After the war, Studebaker built a limited number of Champions based on a more streamlined 1942 first-generation body shell, called Skyway Champions, before its replacement appeared 1947. It was one of America’s first post-war models and body-wise was all-new, with flat front fenders a notable feature of the time. The two-door cars featured a wraparound rear screen and the models later became known as Starlight Coupés. Inside there were such niceties as automatic courtesy lights and back-lit illumination for the gauges. The engine had been enlarged to 2 784 cm3 and delivered 60 kW, which was increased to 63 kW in 1950. At launch, a three-speed, automatic transmission was also offered for the first time. The new Champion was a success and accounted for 65% of the total sales for the automaker in 1947.

At a time when the Big Three restyled their cars every couple of years or so, like most smaller independent manufacturers, mostly suffering from a shortage of funds, Studebaker could only afford facelifts. In 1953, designer Bob Bourke of Raymond Loewy’s studio penned a sleek new coupé and Studebaker quickly asked that the new look be adapted to all 1953 Champion body styles. The two-door was tagged Starlight while the hardtop coupé was called Starliner. Studebaker billed the low and striking Champion’s looks as European, and it was certainly distinctive. The previous model’s 63 kW engine was retained.

But after years of financial problems, in 1954 the company merged with luxury carmaker Packard to form the Studebaker-Packard Corporation and hopes for the company’s future were revived. The same year, a two-door station wagon called the Conestoga was added to the line-up and all models boasted a new grille. In 1955 the Champion’s engine was further enlarged to 3 028 cm3 and delivered 75 kW at 4 000 r/min. The lock-up torque converter autobox was considered to be the most advanced at the time. The grille was changed again the following year, and a wraparound windscreen was introduced while Starlight/Starliner was dropped.

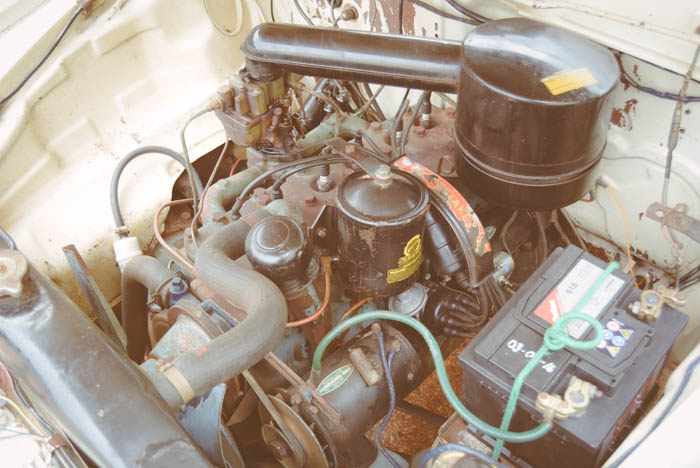

In 1956 the Champions (the coupés were now known as Hawks) were facelifted with different front and rear bodywork, the front fenders boasting eyebrows over the headlights and rear fenders now sporting fins. Electrics became 12-volt. FMM’s four-door sedan featured here is one of these and was first purchased in 1956 by a D R Pretorius from Broderick Motors in Vereeniging. It was built in Uitenhage by SA Motor Assemblers and Distributors Ltd (SAMAD), which also assembled Volkswagen Beetles from 1951 onward.

The car is in an original, well worn condition. It is an attractive ’50s design with fairly balanced proportions, interesting swage lines over the front and rear wheelarches, and a chrome bodyside strip that mimics the kinked waistline and separates the two-tone paintwork. The rear doors are nor particularly wide, though, making entry and exit a bit of a squeeze. Three-abreast bench seats front and rear are trimmed in simply pleated two-tone leather and lift the ambience of what is a light and airy cabin.

This car has a three-speed manual transmission with optional overdrive. It fires readily on the button and the 1 260 kg sedan pulls away with ease. For tall people, limited rearward travel of the front seat means depressing the floor-mounted pedals is ankle-challenging and the column shift gate’s 1st/reverse plane is very close, but once on the move these minor complaints fall away. The big steering wheel is handy when manoeuvring at low speeds but, typically, once on the move the effort required lightens up. Independent front suspension with wishbones and coil springs and a rear axle suspended on leaf springs provide a stable ride with no undue body roll or float. Hydraulic drum brakes proved to be very effective.

But it is the instrumentation that really catches the eye, literally and figuratively. Known as the Cyclops Eye, the speedometer is a horizontally-revolving drum mounted– along with the odometer and indicator warning lights – in a pod on the edge of the dashboard directly above a quartet of dials for amps, temp, fuel and oil. Dials? Well, instead of conventional gauges the dials showed either a green bar if all is well, which changed to red if things were not so good. Space age stuff, but I cannot help but wonder if such innovation did not work against the car’s appeal – a lot of American cars failed simply because they dared to be different.

Sadly, Studebaker’s financial problems started to nosedive and the Champion was phased out in 1958 in preparation for the introduction of the new. But by this time the company had been placed under receivership while it attempted to return to a profitable position. Despite a last-ditch effort to rejuvenate the company with the radical Loewy-designed Avanti, the South Bend, Indiana plant ceased production on 20 December 1963 and the last Studebaker automobile rolled off the Hamilton, Ontario assembly line in Canada on 16 March 1966.

Studebaker deserved to be around longer than it did because it was more than a run-of-the-mill motor company. Its products were contemporary and seldom short on innovation yet despite the best efforts of the Champion model, sadly it simply could not survive in the shadow of the Big Three. MM