30 Jan Anniversary Celebration: South Africa’s first motor race

This month’s anniversary celebration is a deviation from the norm. With Cape Town hosting its inaugural Formula E race on February 25, it’s an opportunity to recall what is generally considered to be South Africa’s first motor race (including an electric car!), which took place almost exactly 120 years ago. Er, but was it actually the first? Mike and Wendy Monk and Derek Stuart-Findlay combine resources and go back in time to reveal the proper story…

When was South Africa’s first motor race? If one accepts that motor racing is ‘a sport involving the racing of motor vehicles for competition’, then the first such event in this country took place in Cape Town in 1900 – but the race only loosely complied with the definition. But the second race certainly did tick all the boxes. It also took place in Cape Town, 120 years ago next month…

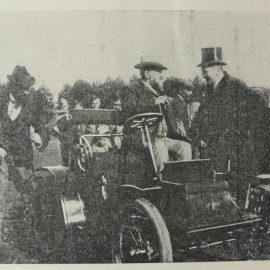

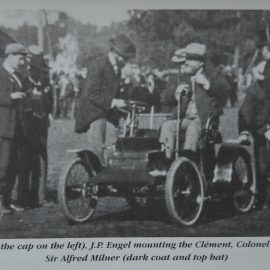

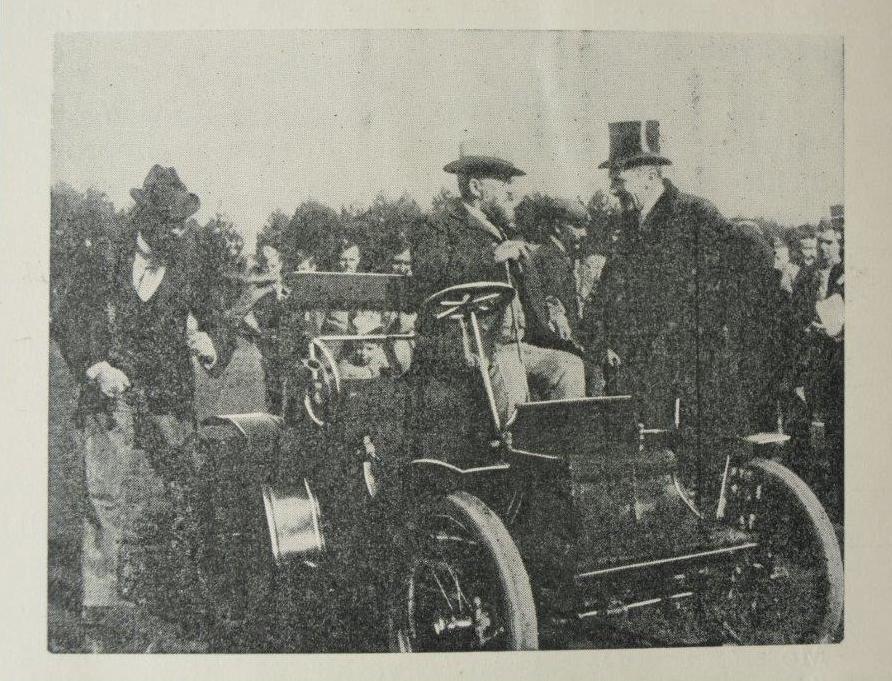

That first race took place on 1 October 1900 at the Newlands cricket ground, which, incidentally, was only five years after the world’s very first motor race that took place in France. His Excellency the Governor of the Cape, Sir Alfred Milner, was present at Newlands and took a keen interest in the race. The Cape Times, in reference to the race, reported that “There were only two competitors, and Mr J P Engel, with his handsome motor easily won the first prize. Naturally, great interest was taken in this novel (so far as this country is concerned) race, and at its conclusion His Excellency the Governor inspected the motor. The Governor expressing a desire to have a ride on the machine, and Mr Engel took him twice round the course at full speed, amid the loud cheers of the spectators, the band playing the National Anthem. Colonel Stowe (the American Consul) then had a couple of turns around the course on the motor, the band appropriately striking up the favourite American air of ‘Yankee Doodle’.

“W M Jenkins was the other competitor. The race was set down for five miles, but the motors started from opposite ends of the field, and there was a condition that on one of the motors overtaking and passing the other, the motor thus taking the lead would be declared the winner. As a matter of fact, it was apparent soon after the start that Mr Engel’s motor was the more powerful of the two, and just after the first mile had been covered it passed the other motor, and thus won the race.”

Regarding the cars, the winning motor was a De Dion-engined Clement, and while nowhere is the other car mentioned it was almost assuredly a steam-driven Locomobile because Jenkins was the sales manager of Garlicks Cycle Supply, the local agent for the make.

The Cape Times report summed up the event thus: “The motor race is an event which marks an epoch in the history of sports meetings in South Africa, it being the first motor race in this country”.

As an aside, in a UK Autocar report of the race the venue was given as the Green Point track. The confusion probably arose out of the fact that the sports meeting was organised by the Green Point Cycling and Athletics Club, and included a one-mile walking race, a sack race and a number of cycling events. The referee was Colonel Stowe and amongst the judges were Jack Rose, Donald Menzies and ‘Yankee’ Jenkins – the other competitor in the motor race.

The second event took place on the Green Point Cycle Track on Saturday 7 February 1903, and was actually more than just a race, it being billed as a ‘Motoring Tournament’. It was organised on behalf of The Automobile Club of South Africa by member and avid motorist Jack Rose to celebrate the club’s first year of existence. The purpose of the event was “to demonstrate the capabilities of the motor car to the public”. In fact, it was not only motor cars that were taking part, but motor bicycles as well.

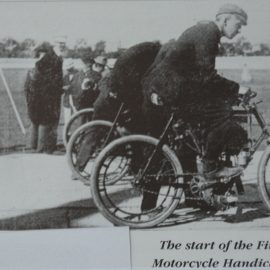

Starting at 14h30, there were nine events on the time table beginning with a 5-mile handicap for motor bicycles before a procession and manoeuvring of cars took place at 14h45. This was “a very imposing and interesting spectacle” with 21 cars stretching back 275 metres being led through a series of spiral movements on the field by Rose. “The ease with which the large and small cars followed the turns and twists was an object lesson in steering,” said the Cape Times.

The programme listed 15 cars to take part in the motor races, namely:

Mr A T Hennessy 14 hp New Orleans

Dr R Aderne Wilson 4½ hp Cudell

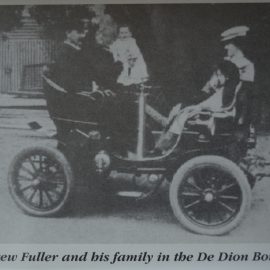

Mr A C Fuller 6 hp De Dion-Bouton

Mr W M Jenkins 8 hp Darracq

Mr J Langley 10 hp Georges Richard

Mr M Irving 6½ hp Gladiator

Mr J G Rose 4½ hp De Dion-Bouton

Mr M Deponte 4 hp Renault

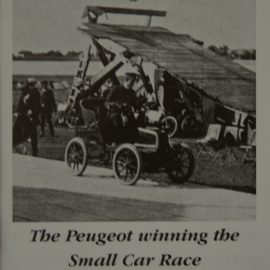

Mr J Courtis 6 hp Peugeot

Mr D Menzies 6 hp De Dion-Bouton

Mr W Porter 4½ hp De Dion-Bouton

Mr E Edwards 7 hp Panhard et Levassor

Mr S H Adams 10 hp Wolseley

Mr H L Jenkins Electric (?)

Mr J Klerk 4 hp Buffalo

Unfortunately, exactly what car Mr Jenkins drove is not known. There were a surprising number of electric cars around at the turn of the last century, so who knows? However, the programme (price threepence) lists the type of body and its colour for each car and the colour given for both Jenkins’ and Klerk’s cars was given as chocolate, which in itself is unusual. But Buffalo, a New York based manufacturer, produced both petrol- and electric-powered vehicles at that time. Seeing as Klerk’s car has a horsepower rating and is therefore a petrol model, could it be that Jenkins had an electric model? The mystery lingers on…

‘Grid positions’ were decided by drawing lots and the race was started with a pistol. Jumping the start would incur a 10-yard (9,1 metres) penalty. Overtaking was only allowed on the outside. Any driver found guilty of ‘foul or unfair driving’ would be disqualified and competitors were strongly warned against ‘trespassing on the lawn’.

Compare that with F1’s weaving and exceeding track limits rules…

Oh, and open betting was not permitted…

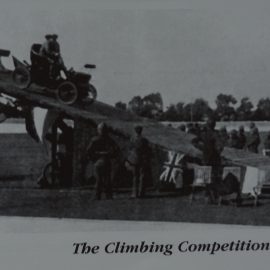

Two three-mile heats for Small Cars up to 6 hp began at 15h15, which were followed by another 5-mile handicap for Motor Bicycles. Then at 16h00 there was a Climbing Competition in which cars had to drive up, stop and start on a large inclined ramp that was adjusted to create slopes of 1:10, 1:8, 1:6 and 1:3. Many cars went up in reverse…

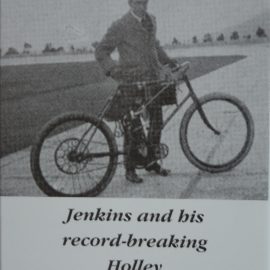

At 16h20 there was a 5-mile Motor-paced Cycle Race that proved to be something of a fiasco “due to the lack of understanding between the cyclists and pacers on motorcycles”. Nevertheless, during one of the races, ‘Yankee’ Jenkins set up a South African one-mile motorcycle race record on his Holley.

A 5-mile Handicap for Large Cars took place at 16h35 in which there was drama on the last lap when Donald Menzies in his De Dion-Bouton overtook Jimmy Langley’s Georges Richard to take the victory.

Next came a Steering Competition at 16h55, which involved the setting out of a number of dummies and tubs representing people, horses and carts and competitors had to manoeuvre amongst them. Andrew Fuller won this event in his De Dion-Bouton.

The final event of the day took place at 17h10, which was the Small Car Race final. John Courtis was the winner in his Peugeot, comfortably ahead of Jack Rose in his De Dion-Bouton.

The highest speed recorded during the afternoon was 32 mph (51,5 km/h). The Cape Times reported that the club was “favoured with glorious weather for their bow to the public”. It was certainly a grand affair, with the band of the 1st Northumberland Fusiliers ‘rendering selections’ throughout the afternoon.

As a footnote, in the evening, the organising club held its first annual dinner in which renowned poet Rudyard Kipling was the guest speaker. Already a keen motorist, he had earned the nickname Mudguard Kipling and the topic of his speech was ‘The Ideal Motor Vehicle for South African Conditions’, his talk creating much amusement amongst the guests.

(NB: Grateful thanks to Derek Stuart-Findlay for sharing his research on the 1903 race. No copyright infringement is intended with any of the images used to illustrate this article.)